Food Miles

Virtually every person in American knows of the Mashpee Wampanoag Nation in Massachusetts, even if not by name. They were the people who shared their food and harvest with the hungry, disoriented, and confused Pilgrims in 1620. Yearly, we eat a meal that is derivative of their foodways, including yams, turkey, cranberry, beans, and pumpkin. Four hundred years after that mythologized Thanksgiving, in 2020 the Bureau of Indian Affairs told the Mashpee Wampanoag people that they were being “de-established” as a reservation, which meant they would have to pay punitive amounts of back taxes on the paltry 321 acres of their ancestral lands that remained to them. Their original lands had extended over hundreds of square miles in Rhode Island and Massachusetts that had been inhabited for twelve thousand years. Although the decision was overturned on a technicality, their status remains uncertain. The lands they hold are crucial to food sovereignty—to their ability to feed themselves from their farms and traditional waters, where they harvest shellfish, crabs, and fish. For them and hundreds of cultures around the world, food sovereignty is cultural sovereignty, and cultural sovereignty is rooted in a deep understanding of the relationship between people and the land and its waters. It is the opposite of Big Ag. It is culturally sensitive because cultures die or thrive depending on the sanctity, health, and integrity of ecosystems.

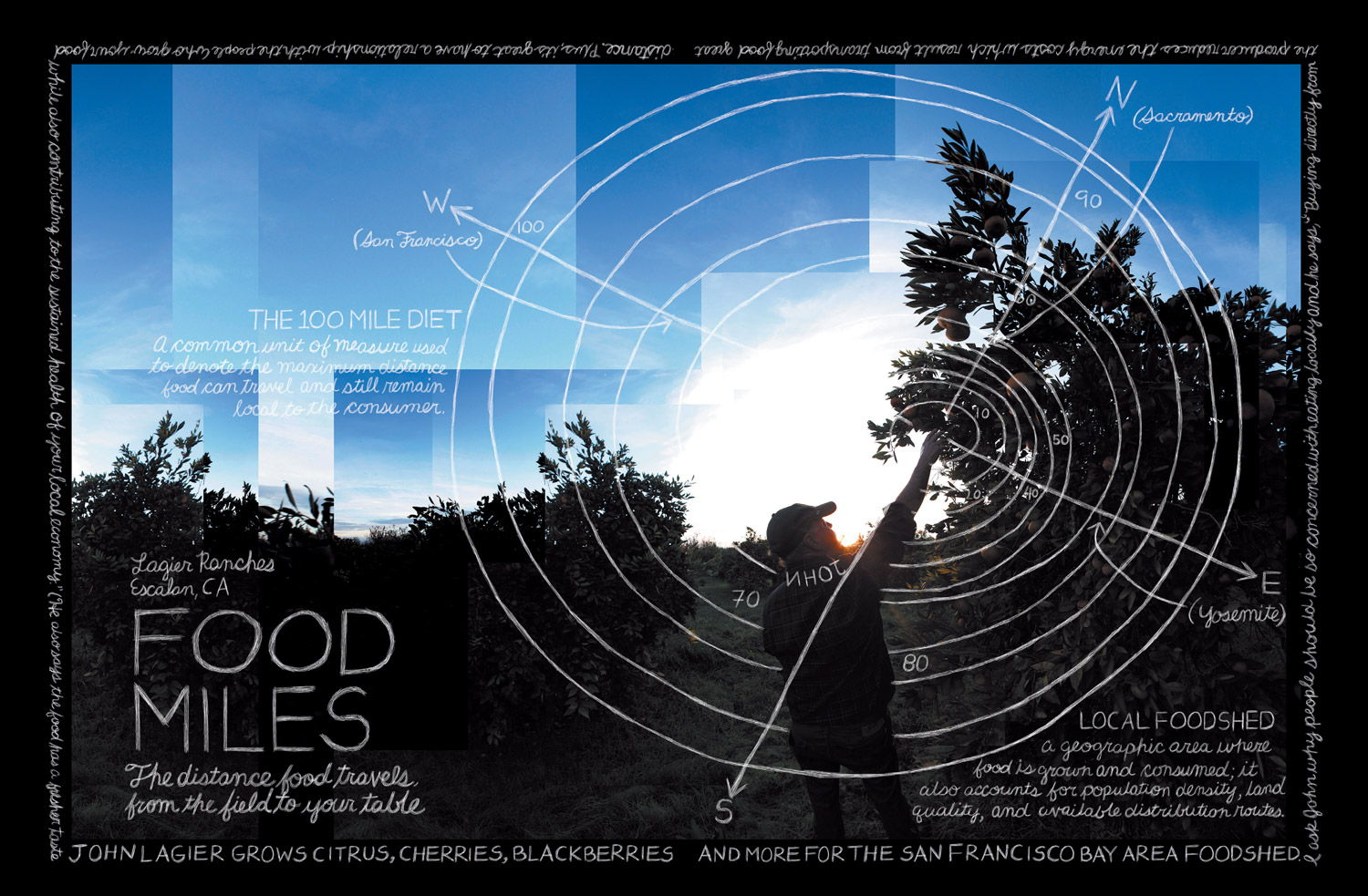

The hundreds of thousands of people in communities across the United States who are relocalizing access to healthy, clean food are not under the illusion that urban or community gardens are sufficient unto themselves. There is a grassroots movement building that wants to literally overturn the current food system, and this can be accomplished only through policy and law. It means ridding schools of fast-food chains and soda vending machines. It means a free lunch (at least) for every child in America. It means removing the inordinate influence of Big Food on school lunch programs, food stamps, and menus. If you live in a food system where most of the food sold makes most of the people sick and dependent on pharmaceuticals—a food system that benefits almost no one except distant shareholders of large companies—it is a system ripe for systemic change. If it is a food system that comes apart in a pandemic, then it is a brittle system that reveals the lack of food security, and that is what localization and food sovereignty address. Whatever you call it, and however localization continues to grow, morph, and permeate cities, towns, and communities, it has a profoundly beneficial impact on the greatest threat to food security—runaway global warming. Acts of localization regenerate the environment, water, children, oceans, soil, and culture.